A few weeks ago I was asked to present at one of the closing events of a project aiming at defining “… future knowledge, skills and competences required by key professionals of the aeronautical sector. By identifying the needs of an evolving labour market, skill-UP develops initial and continuing VET training programmes based on suitable and innovative teaching and training methodologies and on study pathways for skilling, upskilling and reskilling the air transport workforce.” The project is called skill-UP and you can find more here: https://www.skillup-air.eu/

I was asked to consider the future Air Traffic Controller skill set. I took current competence areas and skills and the way we feel the future is going in terms of service expectation, technology and societal trends as a starting point to try to look into the crystal ball and see how this future skill set for air traffic controllers could look like.

I came up with 5 areas which admittedly are not all necessarily skills but are a mix of skill, knowledge and attitudes (known as KSAs) that I believe would be necessary for the future.

The 5 KSAs for me are:

- Digital competence (K)

- Cognitive Flexibility (S)

- Maintenance of current ATCO skills that lead to cognitive processes: Spatial Intelligence, Situational Awareness and Decision Making with possibly alternative exposure to practice. (S)

- Continuous Development (A)

- Discipline (A)

With digital competence I mean that a future air traffic controller will need to appreciate how artificial intelligence (not in the strict sense of AI but in a generic sense of a non-human support/co responsibility in decision making and other processes) works, its strengths and weaknesses not dissimilar to how we inherently learn on how to work with other people and to get a feel of their strengths and limitations.

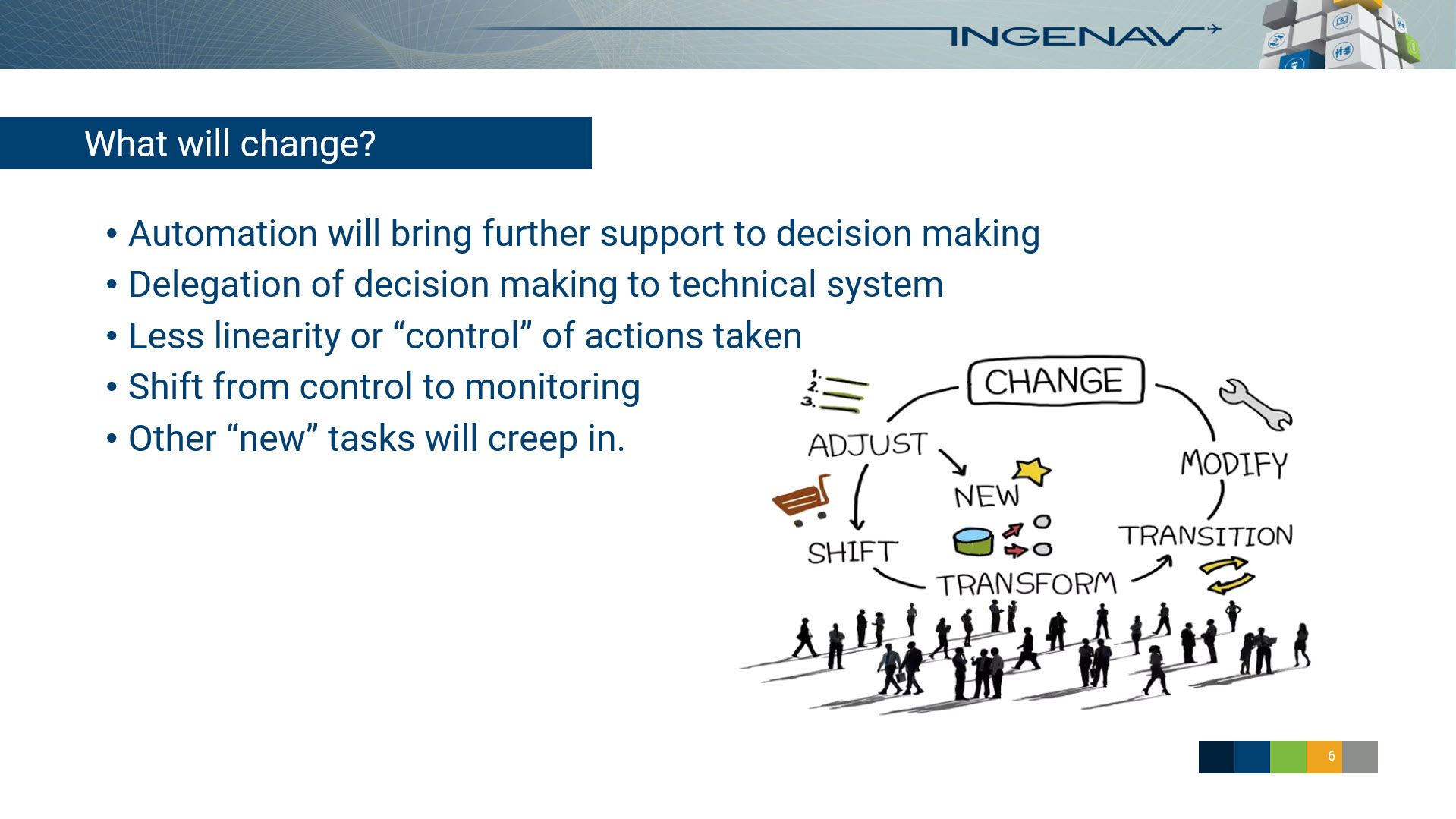

With cognitive flexibility I mean that skill to be able to switch from one thing to another and also to go from 0 to 100 in a split second. This skill is already important now but if future air traffic controllers will be put in montoring situations, then we will need to fill in the gaps more rapidly than we perhaps do today.

Future air traffic controllers will still need to take decisions on aircraft flying in 3 dimensions, in order to provide a safe and efficient service. This needs a number of skills to be developed and maintained. Currently controllers mainly maintain these skills by practicing. If practicing becomes less available, because of the delegation of certain elements of work to an automated system, then we will need to find an alternative way on how to maintain these skills – (apart from the fact that as a system we need to acknowledge skill degradation and have mitigations for these that do not expect super being skills from human air traffic controllers – but that is the subject of an other article)

I included continuous development because I think that the job of a controller will be changing rapidly in the future. If future controllers do not endorse the attitude that they need to keep learning and to move with things, then we will have a mismatch in pace.

Finally, I also included discipline as an attitude. One may say that discipline is important to date and I would perfectly agree. However whereas in the present there are still windows which allow one to work in their own bubble and do “what they like and how they like” within a set of prescribed rules and regulations, the trend is towards sharing of information and collaborative decision making, between humans and between humans and machines. The discipline comes in where it will become more important to do the right thing, but in the way it fits with the rest of a shared system rather than in isolation. Working well with others, vs working alone requires discipline. Tomorrow´s air traffic control work will probably require even more of that.

These are my thoughts about the future skill sets of air traffic controllers.

I end by sharing the presentation I gave (click on the picture to go to the pdf).

What do you think? Send me a private message or start a healthy debate. I´ll be happy to answer and to contribute!